The Chilean Coup at 50: The Ever Delayed Spring

Or: Having to write about the things you don't want to write about.

September is, as one of my History teachers at school once said, a month which puts us Chileans into a mystic mood. A month in which one too many anniversaries converge, at the same time the Spring gets started, in one of the few Latin American countries which experiences actual seasons through most of its geography. The transition from Winter to Spring is rather abrupt, generally by the second week of September it is clear and bright outside, temperature hits the low to mid 20º C and most trees are in bloom. Climate change has moved that timetable a few weeks earlier, but in general, the country is ripe and ready for the Independence Day celebrations on the 18th and 19th of the month. It’s our Carnival, in a country that never had the resources to celebrate a proper Carnival*. Thus, the Independence Day became our Carnival, a week-long celebration (with a few extra days here and there) of the Nation and whatever cultural constructs we have elevated as core parts of our identity. In practice, it means gobbling up liters of red wine, chicha and barbeques, but it’s still awesome. It doesn’t take an anthropologist to say that it is, symbollically, a celebration of the end of Winter, of having survived the better 75% of a year (well, it’s not like the winters in most of Chile are that harsh). The celebration acquires a whole layer of meaning in being wholly republican, in the sense that it celebrates the birth of brand-new country and republic, breaking away from the shackles of being a colony to a monarch. The Independence Day celebrations are so much more than just our alternative to a Carnival, praise our Founding Fathers, in their sensible wisdom, for choosing to celebrate them not when the actual declaration of independence was signed (January 2, 1818), but on the day the first Government Junta was celebrated, declaring Chile’s autonomy from the French-controlled Spain, a very cautious first step on the way to independence. Whatever, it worked. A whole month devoted to our history.

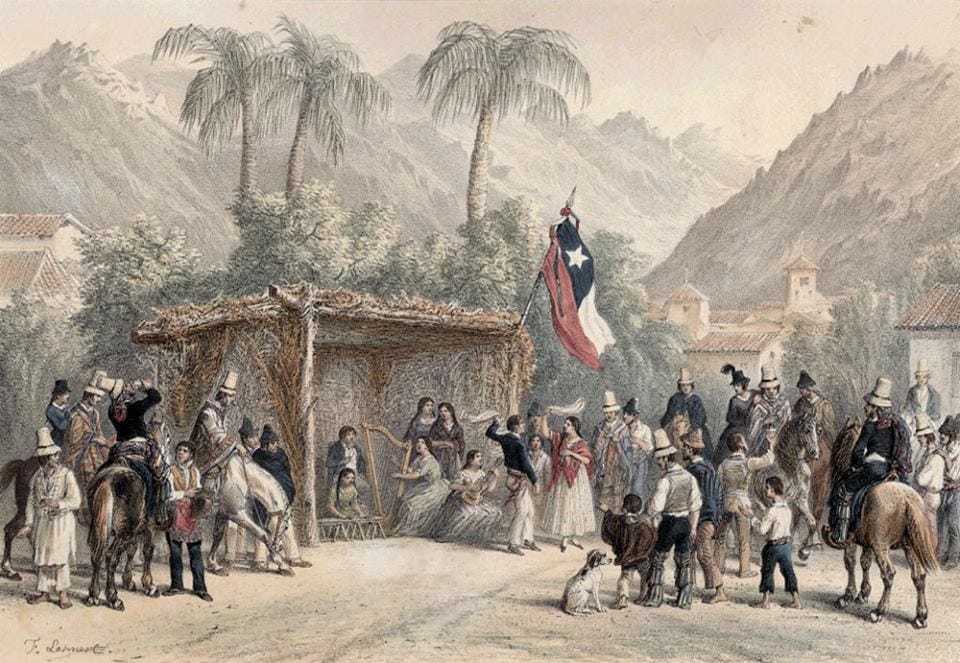

Claudio Gay. Chingana. Atlas de la historia física y política de Chile

Now, picture yourself in our Septembers, the National Holidays as we call them: Every building and house has the flag on public display. There are paper wreaths and plastic stripes, always in red white and blue, hanging from the celings and framing the windows of every supermarket, small shops and restaurant. Smell of grills, tomato and onion salad, syrups and hay. If you’re lucky, you’ll be at places where they make an effort to play Chilean music other than the boring-ass traditional cuecas. The kids are taken to school, poor things, having to dress up in what are supposedly "Chile traditional dress”, the huasos and chinas, our local version of the cowboy (which is actually just representative of just the Central Region). Still, it’s awesome. All of those smells and sights, living history and pastiche history flooding into you in a way that is intoxicating but also affirming. Because even if you try to use the month as a platform to to critically examine your history and heritage as a Chilean, in the classroom or wherever, every resistance you put up is ultimately pierced by the smells, the colors, the music. You are being invited, first, to a celebration of Spring and rebirth, probably the very first thing we as humans celebrated, while also celebrating the origin of your identity as a person from a country, kind of important too.

Now you begin to realize why Chileans get all mystic about September.

Israel Roa. Fonda en Parral. 1940.

And that’s when…

title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" allowfullscreen></iframe>

You remember that exactly one week prior to the 18th, in a perpetual September, the Chilean Military and its civilian aristocracy decided to barge into our History (not for the first time) to enforce their own holiday. In their words, “recovering the country”, as if they had ever lost an inch of their footing, as if they had ever yielded any scrap of power or capital ever since the country became independent. The democratically elected government of Socialist president Salvador Allende was overthrown after three years of a concerted effort to undermine it, with the help of the US Government, the CIA, other Global Powers and the Chilean Elite. The political incompetence of member of his government and the scattered actions of far-left groups didn’t help to stabilize things before the coup, but even if Allende’s government had been more effective, the plan to overthrow him and the movement behind him would’ve taken place. Because this movement, the Unidad Popular, was more dangerous than any of the other Socialist, revolutionary projects that were taking place at the same time, as it set itself to prove that you could bring forth these transformations while in a Democracy, while having an active opposition and respecting the rule of law. A fairer, modern, healthier and educated country through politics and mass organization, eschewing the need for violence. A Chilean Spring that started on November 3 of 1970, with the assumption of Allende to the Presidency, a Chilean Spring that was almost immediately delayed. An Ice Age followed, a perpetual high pressure front that remains in place to this day. It begun subsiding around the Spring of 1988, we thought for a minute that it would go away, but then came back again, not with a vengeance, but with the persistence of a perennial bronchial disease.

An Ice Age that came, took close to 4,000 lives directly, stole thousands of children, tortured and exiled hundreds of thousands and broke a country’s heart. And it became the intergenerational trauma that seeped into every single household and family, saddling us not only with the legacy of direct violence, but with economic structures that perpetuate the violence of the regime to this day, despite three decades of Democracy and reforms. The kind of events that while leaving no family unscated, we have a hard time trying to talk about. And in my family we always talked about about the coup and the dictatorship… if by family we limit ourselves to me and my mum. Going further from that circle, the more correct terms we could use are “scream” and “yell”.

It’s an intergenerational trauma that is hard to talk about, so I guess all I can do for now is write about it. Because this anniversary is a multiple of 10, and multiples of 10 compel you, but more so the multiples of 100. And for this 50th anniversary, and as this blog-thing is aimed squarely at Anglophone readers, I have three issues to tackle in this glorified therapy session: What made the Chilean dictatorship “different” from other Latin American coups; What to do when the people that deny and justify these heinous crimes are in the mainstream… and in your family; and what role Memory plays going forwards.

Here’s a track to get started.

*(Except for the Northern Regions, but those hadn’t been… “incorporated” into the country at the dawn of Chile’s existence)